Read GK’s newest insight paper on the Government’s Levelling Up White Paper here: Levelling Up White Paper Insights

To discuss what the White Paper means for your business or investments email jack@gkstrategy.com to fix up some time.

Read GK’s newest insight paper on the Government’s Levelling Up White Paper here: Levelling Up White Paper Insights

To discuss what the White Paper means for your business or investments email jack@gkstrategy.com to fix up some time.

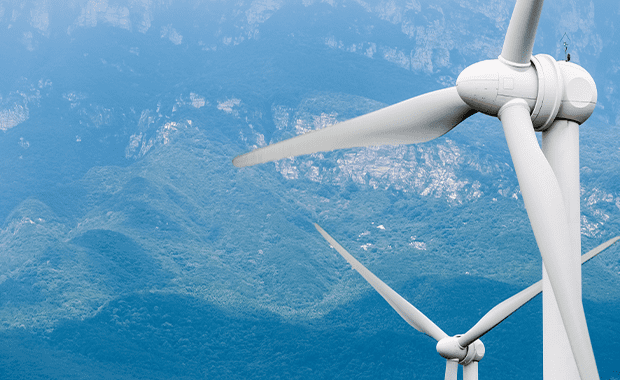

Annual contracts for difference – how will this impact the UK’s renewable energy generation?

Amidst a worsening energy and cost-of-living crisis, and ongoing pressure from within the Conservative Party in the shape of the Net Zero Scrutiny Group, earlier this month the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy has made one of its biggest statements to reaffirm its commitment to the development of the renewable power industry in the UK. In line with commitments in the 2021 Net Zero Strategy, the Department has taken the decision to hold Contracts for Difference (CfD) auctions on an annual basis from March 2023, rather than every two years as previous.

The scheme is the Government’s flagship policy for the deployment of low-cost renewable energy, which incentivises investment into renewable energy generation by providing energy providers with stable and predictable returns on their supplies. This is achieved through long-term contracts of 15 years, where two parties — a renewable energy supplier and the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC) — agree to pay the other party for the difference between the market price and the value which the parties agreed at the point the CfD was entered – the strike price. For example, when the price for electricity dips below the strike price agreed with the government as part of a developer’s CfD, the developer will receive a ‘top up’ to the level of the strike price, and vice versa.

This significantly reduces the investment risk for developers, and allows them to borrow money more cheaply, accelerating the development of low-carbon technologies and crucially continuing to drive down the costs of generation. This can act as the catalyst of continual development for the UK’s renewable energy market, creating optimal conditions for consistent private investment into the landscape.

These developers will be crucial pillars for the UK’s net-zero strategy, not least because of the UK’s lofty target to reach 40GW of wind power capacity by 2030. The scheme has clearly already had an effect. In 2010, total capacity was 5.4 GW. By 2020 that figure had more than quadrupled to 24 GW, after the scheme was introduced in 2013 on a bi-annual basis.

So why the need to scale the scheme up to annual rounds of bids? One of the biggest factors behind this is undoubtedly UK energy security. The Government has painfully learnt the complications and difficulties of being dependent on supplies of natural gas from the European continent for a significant portion of the UK’s energy supply, with considerable strain now being felt by the British consumer. Increasing the frequency of CfD auctions will increase the number of opportunities for developers to engage with the scheme, helping to provide a diversified power supply and support the UK’s long-term energy security. The decision will also dramatically lessen the burdens for renewable energy companies, who will be able to take advantage of the regularity of auctions rather than having to navigate the two-year periods of uncertainty between the CfD auction rounds.

Fundamentally, this move is a positive one for both supplier and consumer. The annual rounds of contracts greatly ease the strain on renewable suppliers, providing developers with the assurance that their risks will be minimised and incentivises continued investment into the UK. The subsequent scale-up of renewable energy into the grid will mean that there is much greater flexibility in the system for consumers to help shield them from future price shocks and advancing the UK’s Net Zero credentials further.

The fast-paced nature of this environment will create a strong platform for engagement with Government. GK Strategy has extensive experience of advising governmental engagement and helping businesses take advantage of existing opportunities within the energy policy landscape.

For more information, get in touch with milo@gkstrategy.com.

GK Adviser, and former Health Minister, Phil Hope shares his thoughts on the Government’s proposals for health and care reform in our newest blog ‘Integration White Paper Joining up care for people, places and populations: A genuinely radical leap forward’

Read Phil’s thought’s here: Integration White Paper – Joining up care for people places and populations

The Omicron variant, parliamentary scrutiny and a distracted Government are all hindering the development of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) and there are concerns about the framework that sits around them.

Amidst the capacity and workforce pressures faced by the health service this winter, longer-term ambitions for the transformation of our health and care system are also feeling the strain.

The timelines for formalisation and statutory responsibility of the 42 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in England have been pushed back. The intention is now for them to be given their full statutory responsibilities by 1st July this year rather than 1st April as originally planned. The primary reason given for this delay is to allow parliament an acceptable amount of time to review and approve the proposed changes.

Even with this extension, there is growing frustration that this wholescale reconfiguration of the health system is not being accompanied by the required due diligence and planning.

The Health and Care Bill – the legislation that will enable these reforms – has reached the House of Lords and the early signs are the Government are in for a bumpy ride.

It’s times like this where the second chamber can demonstrate both its value and its limitations. More sector specialists, less constrained by time pressures and careerism often makes for a better assessment of the changes proposed. Any substantive improvements to the legislation are likely to come from the Lords, the challenge or opportunity depending on your perspective is that any amendments must be approved by the Commons, where the Government has a strong majority and can whip MPs effectively. Therefore, sensible Lords amendments may well be reversed prior to the Bill receiving Royal Assent.

The concern for the Government is that the Lords are starting to highlight that the legislation is poorly planned and drafted. In the Autumn of 2021, Health Secretary Sajid Javid admitted that “significant areas of contention” had yet to be resolved with the reconfiguration of the health system the Bill and he’s being proved right.

The initial assessment from the Lords has been both scathing and embarrassing for the Government. the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee has stated that the Bill “falls so short of the standards which the Committee — and Parliament — are entitled to expect” and the legislation is a perfect example of a wider issue of “how much disguised legislation a Bill can contain and offends against the democratic principles of parliamentary scrutiny”.

Furthermore, just as the Bill was due to begin its Committee Stage the Lords Shadow Health Spokesperson, Baroness Thornton, also identified that proceedings couldn’t legally begin without an impact assessment related to parts of the legislation. The Government has apologised for the oversight and the very short notice that they were shared.

Taken together, these issues all add to the impression that the reforms are being rushed through, at a time of extreme pressure on the health system with not enough evaluation of the impact and practical implementation of new powers and accountabilities. The biggest concern among those who favour greater health devolution is that the Bill will reinforce the instinctive tendencies of the government and NHSE towards greater centralisation and prescription, and continued NHS dominance of the health and care agenda.

During January and early February 2022, the Lords will undertake a line-by-line examination and vote on each clause of the legislation – including the long list of amendments tabled by Peers.

Trying to predict which amendments will garner enough support is difficult – let alone which the Government may concede on – but topics that have high profile backers and cross-party support include:

Of course, it’s not just the Parliamentarians that are frustrated, many ICS leaders – preparing to go live with their accountable duties – only found out about the delay via third party sources with the Department of Health & Social Care and NHS England’s communications leaving much to be desired. Louise Patten, Chief Executive of NHS Clinical Commissioners recently outlined that that the delay causes confusion about local leadership responsibilities and partnership working with local government and threatens accountability.

Moreover, the delay in publication of the Integration White Paper, further guidance on developing place-based Integrated Care Partnerships and the Levelling Up White Paper also means that many areas are continuing to develop new local partnership governance arrangements in the absence of a national policy framework.

And of course, all of this hugely matters to patients, the healthcare workforce and organisations trying to supply the health system with the services and technology it needs.

Organisations with a stake in health care delivery need to ensure that they monitor the passage of this legislation and importantly seek the practical understanding of where accountability and commissioning responsibility lies within ICS ‘footprint’ regions.

For further information about the implementation and impact of ICS’, please email joecormack@gkstrategy.com

GK’s defence and security expert, Scott Dodsworth shares his thoughts on National security and foreign investment in the UK economy

To discuss further, email Scott@gkstrategy.com

At the start of 2022, we asked our GK Team to give us an insight into how they think the next 5-years will pan out.

Milo:

Wes Streeting leader of the Labour Party in a formal coalition government with the Liberal Democrats after a general election in Spring 2024, with a re-strengthened ‘red wall’ and the informal support of the Scottish Nationalists on the condition of an independence referendum – which will be lost by the Nationalists. Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom despite Sinn Fein winning Irish elections in 2025.

Joe:

In 2027 we’ll have a minority Labour Government or Progressive Coalition elected on a mandate to fix public services, improve creaking infrastructure, and restore financial security for millions of people.

In healthcare, new Integrated Care Systems and Partnerships will have improved link between different parts of the NHS and a greater emphasis will be placed on holistic care. Workforce recruitment and retention will finally have turned the corner, but a solution for a more equitably funded social care system will still be missing.

Iain:

I think we’ll be in another period of coalition government in five years’ time as, on current form, there will be no outright winner of the next general election. If so, it’s likely to be a period (as with the previous coalition) in which potential constitutional changes loom large.

In terms of policy issues, I think there will be real frustration (which could, alas, lead to some political polarisation) that:

Positively, the widespread introduction of driverless cars will be looming, which could transform the quality of life of millions of Britons – especially the elderly.

Finally, there will be a national (well, English) feelgood factor as Jurgen Klopp becomes the England football manager – leading to the team actually winning something, at last, and assured ‘national treasure’ status for the man himself!

Will:

Boris Johnson will lead the Conservatives into the General Election to be held in May 2024, resulting in a hung Parliament and Labour narrowly the largest party in the House of Commons. Johnson largely recovers his own personal position during the remainder of this Parliament, but recent sex scandals among his MPs prove to be the tip of the iceberg, with further and more serious revelations destroying any hopes for the Conservatives remaining in Government. Johnson will be the last Conservative Prime Minister for a generation, as the minority Labour Government introduces electoral reform as the price for Liberal Democrat support, ultimately leading to a splintering on the right of British politics.

The union of the United Kingdom will continue to come under significant pressure during the course of the next five years, but Northern Ireland – not Scotland – will be the first to break away from the UK. Despite this, Brexit more generally will come to be viewed as an economic success, with at least one other EU member state holding a referendum on EU membership within the next 5 years.

Sam:

By 2027, I expect the Labour Party to have built substantial political momentum and to have eroded the Conservatives’ majority in Westminster, formulating a progressive coalition on a mandate of investment in green infrastructure and renewables, modernising and investing in the NHS, and developing an education system that puts the needs of children at the centre. As part of this, I expect the devolution agenda to have been given more substance, which will see lessons learned from Welsh Labour, and more powerful combined authorities across the UK begin to emerge, allowing powers for education, health and care, and planning decisions to be taken into the hands of local people in pursuit of levelling up the UK.

Louise:

Post a general election with no landslide victories – new leadership across both parties. And a women heading up the Labour Party

At least 5 departmental rebrands ….

GK will be staffed by some of the great interns from I Have a Voice making our business more diverse

PE investing in emerging regulatory deals – and GK advising on the political, policy and regulatory aspects of fintech, greentech and more.

Reconsideration of our role in Europe – still out but with closer working

Lavinia:

In five years, there will be the bittersweet realisation that leaving the EU brought more regulatory headaches than benefits. While returning to the EU will be still a question mark, the five-year from now government hopefully will understand the importance of maintaining close relationship with countries near the UK

Dani:

In 2027, the majority Labour Government attempts to further foster the UK’s relationship with the EU to counter the variegated complexities in international relations caused by Russia’s and China’s expansionalism and military threats. In addition with the reality of climate change and a persistent global food crisis, the UK Government and it’s people, who are enjoying a period of economic boom following a recession which decimated the Conservative party, vow to tackle both. Working with western nations who so far have prioritised domestic inward investment, innovative and renewable businesses will be given the platform to invent, change and benefit society as a whole.

Scott:

After the next General Election, the Conservative Party will be the largest party but fall short of an overall majority. They will form a government with the support of the DUP, who in Northern Ireland will face the prospect of a united Ireland, largely caused by years of frustration over the EU border and changing attitudes towards links to Great Britain.

The Conservative Party will, however, be led into the next General Election by a different leader, Johnson’s resignation will allow for the fourth renewal of the party in 15 years. The Labour Party will make gains but fail again to reconnect with its former heartlands in Scotland and the North of England. Labour, Liberal Democrats and Green Party will all face a period of introspection as they rethink their proposition to the country.

English nationalism will continue to threaten all the main parties. Scotland has voted for independence, via a referendum granted by Holyrood not Westminster, leading to protracted legal challenge in the Supreme Court frustrating the will of the Scottish people.

Robin:

Another coalition government, this time led by a woman.

Scotland devolved even more powers and autonomy to ward off independence.

Gk to be operating across the globe.

Pension age raised to 72.

England win the world Cup with Sir Alex Ferguson coming out of retirement and managing England to victory.

Sam:

By 2027, I expect the Labour Party to have eroded the Conservatives’ majority in Westminster, formulating a progressive coalition on a mandate of investment in green infrastructure and renewables, modernising and investing in the NHS, and developing an education system that puts the needs of children at the centre. As part of this, I expect the devolution agenda to be given more substance, which will see lessons learned from Welsh Labour, and more powerful combined authorities across the UK begin to emerge, allowing powers for education, health and care, and planning decisions to be taken into the hands of local people in pursuit of levelling up the UK.

Natasha:

In the short term, price rises will eventually subside and supply chains will be strengthened as a result of shocks dealt during the pandemic and war in Europe. Ongoing energy instability and factional infighting will produce more and more hung parliaments, the result of which will surely be a progressive coalition scrapping first past the post and instituting proportional representation. Expect more conversations about alternative constitutional arrangements as the clamour for more independence referendums and debates about English devolution and ‘devo max’ come back to the top of the agenda. In 5 years time it is likely all urban areas will have directly elected mayors, complete with increased powers to raise and spend money locally.

Speaking of referendums, I expect one on net zero, which will be won by a coalition of progressives, giving them a mandate to institute radical (and necessary) climate policy, starting with the mass insulation of all homes. Finally, the House of Lords turns into a federal, elected upper house, able to wield a veto on bills that impact the constitutional settlement, but with no remit to vote on bills that relate to money or public finances.

Nicole:

With China, India and Russia increasing their spheres of influence (although Russia will continue to decline) as well as the economies of the former two world powers rapidly growing, the remaining Western liberal democracies will continue to ramp up cooperation on security, economy and other policies. This will result in the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, Ukraine to the EU and increased reliance of 5 Eyes.

Moreover, with these growing giants, we will see a world turning to populism and nationalism, which will affect the usual suspects but also turn the US back to the GOP, Canada trusting the Conservatives again following the progressive reign of Trudeau, and the UK carrying on with the Tories despite the Boris administration’s scandals, albeit under a different leader.

Josh:

The Conservative Party will be badly wounded by a failure to implement the proposals in the ‘Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill’ to the satisfaction of voters, leading to a hung Parliament after the 2024 General Election. However, the Labour Party will only have limited success in putting the ‘Red Wall’ back together as recent Conservative efforts to woo South Asian voters bear fruit. Both parties will struggle to reconcile shifting voter bases as the effects of voter realignment become more noticeable.

This will lead to further splits on ‘the Left’ as the Labour Party struggles to create coherent social policy that is palatable to both younger, middle-class voters and older, working-class voters, who had previously considered themselves Labour’s core demographic. As a result of Boris Johnson’s lack of ideological focus, the Conservative Party ‘overcorrects’ after his resignation, lurching rightwards in order to energise grassroots activists and quash any attempts by other parties on ‘the Right’ to steal voters away. The increasing use of ‘culture wars’ by the Conservatives, arising from this overcorrection, will resonate with some disillusioned former Labour voters and partially blunt messaging from the Labour Party, but it is also likely to push traditional Tory voters from the ‘shires’ towards the Liberal Democrats.

On the policy front, the FCA will advocate more vigorously for the increased use of RegTech by firms to adjust to the proliferation of new technologies and the pressing need to create a more structured regulatory environment. The Government will also promote more public/private schemes to encourage the building of RegTech ecosystems to ensure greater compliance and potentially facilitate cross-border investments that could boost UK-based start-ups.